Ever find yourself forgetting things exist just because they’re not right in front of you? Like that awesome sweater you bought last fall or maybe those important documents you tucked away for safekeeping?

“Object permanence” is a cognitive idea that might help you find your way through this fog.

In simple terms, object permanence is the understanding that objects continue to exist even when they cannot be seen, heard, or otherwise sensed.

This blog delves into how people with ADHD may struggle with object permanence, why it matters, and ways to strengthen their object permanence.

What is object permanence?

First off, let’s break down what permanence means for objects. In psychology, the definition of object permanence refers to the understanding that objects continue to exist even when they cannot be seen, heard, or touched.

In essence, object permanence allows us to hold onto the idea of something’s existence even when it’s not directly in front of us.

An example of object permanence is when you place your keys inside a drawer, and hours later, you still remember where the keys are even though you can’t see them.

As part of his theory of cognitive development, Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget first introduced this idea. At its core, object permanence is a cognitive milestone reached during infancy, generally around 8-12 months old.

As an illustration, a baby who understands object permanence will search for a toy hidden under a blanket, knowing it hasn’t disappeared but is simply out of sight.

Why does object permanence matter for ADHD?

If you have ADHD, you’re probably familiar with that “out of sight, out of mind” phenomenon. Sometimes, you can even ask, “Are people with ADHD that forgetful?”

In the case of people with ADHD, it’s not that you don’t have the understanding that something exists. It’s that you easily forget about it without any helpful cues to help you remember.

Imagine your brain as a cluttered desktop. Important files (tasks, objects, people) are there. But unless they’re on the top of the pile, they might as well not exist. This can lead to forgetting appointments, misplacing belongings, and even neglecting important tasks.

This can contribute to the lack of object permanence, referred to as object impermanence, in ADHD adults. It’s one of the hidden symptoms of the ADHD iceberg.

Examples of object impermanence in adults with ADHD are:

- Out of sight, out of mind: Items or tasks not immediately visible can be easily forgotten, leading to misplaced objects or incomplete tasks.

- Difficulty with planning and organization: Keeping track of future events or deadlines can be problematic, impacting personal and professional life.

- Emotional object permanence: Relationships and social interactions can also be affected. Adults with ADHD may struggle to maintain emotional connections with others when they are not physically present.

But why does it happen?

Research into ADHD suggests that the brain’s executive functions—those that manage planning, focus, memory, and impulse control—are affected differently than in neurotypical brains.

The prefrontal cortex, which plays a significant role in these executive functions, including working memory, often shows delayed maturation or different activation patterns in ADHDers.

Working memory helps us reason, comprehend, and learn. Basically, it lets us use new information while doing something.

When our brains struggle to maintain an active representation of items that are not directly in front of us, it affects our ability to recall and manage these items effectively.

Object permanence in ADHD vs. Autism object permanence

Autism and ADHD (AuDHD) can both affect cognitive functions, but they do so in very different ways when it comes to object permanence.

In ADHD, it’s not the understanding of object permanence that’s lacking but rather the ability to maintain focus on information that is temporarily not in use.

Imagine placing your phone on a stack of books while your brain is buzzing with different thoughts and tasks. Later, you can’t recall where the phone is.

It’s not that you believe the phone ceased to exist, but your mind didn’t prioritize storing the information. Why? Because of the many things vying for attention.

Within the autism spectrum are a number of conditions that can make it hard to communicate, interact with others, and control repetitive behaviors. A person with autism may also have changes in how they see and interact with the world around them.

Some people on the autism spectrum might not feel object permanence in the same way.

One theory suggests that difficulties with object permanence might relate to the challenges some autistic individuals have with understanding and predicting the perspectives and beliefs of others.

A child with autism might become upset when a toy disappears from view because it’s challenging for them to understand that it still exists. It’s not simply forgetfulness but a different processing of how objects in the environment are understood and internalized.

How lack of object permanence affects daily life for ADHDers

1. Lack of object permanence in ADHD & relationships

Object impermanence in ADHD can affect the emotional landscape of relationships through inconsistent attentiveness. Loved ones might feel neglected or forgotten, thereby straining connections.

At home, ADHD object impermanence can show up as leaving chores halfway done, missing important family events, or losing personal items. All of these can cause stress and tension between family members.

Attention changes do not show how much someone loves or cares for them; they are just a result of the way their ADHD brain is wired.

2. Emotional impact

People with ADHD who have object impermanence may feel frustrated, embarrassed, or even guilty when they have to deal with their symptoms every day. It can feel like you have no control when you lose important things. Or forget to do important things. It can all cause feelings of anxiety and low self-esteem.

3. Professional life

In a work environment, object permanence issues in ADHD can manifest as missed deadlines, forgotten meetings, and incomplete projects. This can affect job performance and professional relationships. It may make it crucial to find effective strategies for managing these challenges.

Ways to deal with ADHD object impermanence

Alright, now that we know what we’re dealing with, let’s talk strategies.

Here are some practical tips to help you keep track of things even when they’re out of sight:

- Sticky notes: Classic but effective. Use colorful sticky notes as a reminder of everything important to you. Or for your upcoming task in your workspace or kitchen.

- Whiteboards: Write down tasks and important dates on a whiteboard in a frequently visited area.

- Designated places: Create specific spots for items you frequently use and lose. Keys go on the hook, shoes by the door, etc.

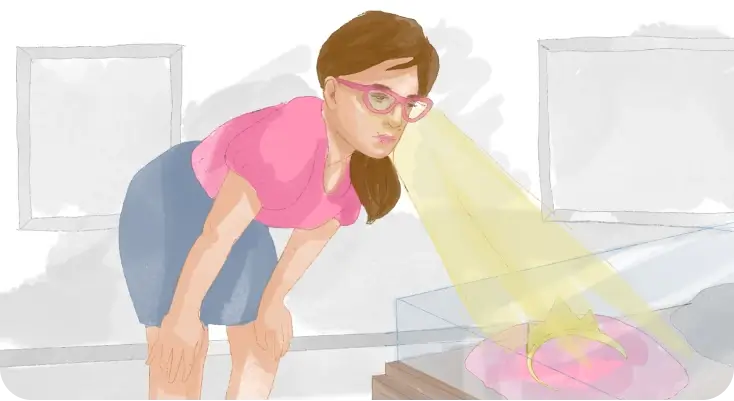

- Clear storage: Use transparent bins and boxes. If you can see it, you’re less likely to forget it exists.

- Consistency is key: Try to build routines where you consistently place or check for items. This can help your brain develop a habit, making it easier to remember.

- Stay connected: Make an effort to regularly check in with loved ones through calls, texts, or social media.

- Visual cues: Keep photos or mementos of important relationships where you can see them to reinforce emotional connections.

Peekaboo, I See You!

To sum up, the concept of object permanence and ADHD does more than explain a child’s peek-a-boo experience; it provides insight into the cognitive processes that can be particularly challenging for those with ADHD.

By recognizing the implications of this concept, we can develop better tools, routines, and awareness. This is not only for those managing ADHD but also for anyone aiming to enhance their organizational skills and working memory.

By acknowledging and adapting to the nuances of how our minds work—in the physical world as well as digitally—we unlock greater potential for productivity, stability, and well-being.

Remember, the path to improving our cognitive world begins with the simple acknowledgment that what is out of sight need not be out of mind.

Disclaimer

This article is for general informative and self-discovery purposes only. It should not replace expert guidance from professionals.

Any action you take in response to the information in this article, whether directly or indirectly, is solely your responsibility and is done at your own risk. Breeze content team and its mental health experts disclaim any liability, loss, or risk, personal, professional, or otherwise, which may result from the use and/or application of any content.

Always consult your doctor or other certified health practitioner with any medical questions or concerns

Breeze articles exclusively cite trusted sources, such as academic research institutions and medical associations, including research and studies from PubMed, ResearchGate, or similar databases. Examine our subject-matter editors and editorial process to see how we verify facts and maintain the accuracy, reliability, and trustworthiness of our material.

Was this article helpful?